2.1 Harrod–Domar model

The Harrod–Domar

model is a Keynesian model of economic

growth. It is used in development economics to explain an

economy's growth rate in terms of the level of saving and of capital. It suggests that there is no natural

reason for an economy to have balanced growth. The model was developed

independently by Roy F. Harrod in 1939,

and Evsey Domar in

1946, although a similar model had been proposed by Gustav Cassel in

1924. The Harrod–Domar model was the precursor to the exogenous growth model.

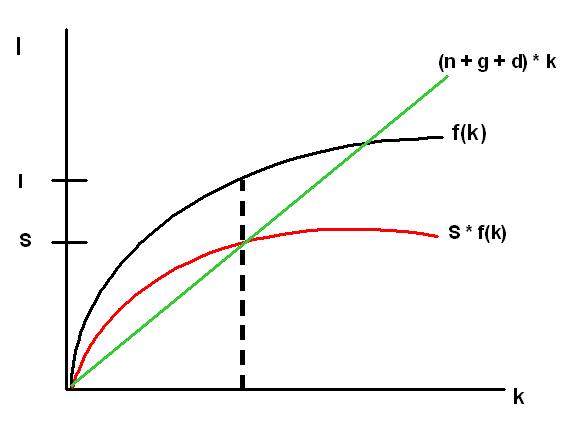

Neoclassical economists claimed

shortcomings in the Harrod–Domar model—in particular the instability of

its solution—and, by the late 1950s, started an academic dialogue that led to

the development of the Solow–Swan model.

According to the Harrod–Domar model, there are three

kinds of growth: warranted growth, actual growth and the natural rate of growth.

The warranted growth rate is the rate of growth at

which the economy does not expand indefinitely or go into recession. Actual

growth is the real rate increase in a country's GDP per year. (See also: Gross domestic product and Natural gross domestic product).

Natural growth is the growth an economy requires to maintain full employment.

For example, If the labour force grows at 3% per year, then to maintain

full employment, the economy’s annual growth rate must be 3%.

Although the Harrod–Domar model was initially created

to help analyse the business cycle, it was later adapted to explain

economic growth. Its implications were that growth depends on the quantity of

labour and capital; more investment leads to capital accumulation, which

generates economic growth. The model carries implications for less economically developed countries,

where labour is in plentiful supply in these countries but physical

capital is not, slowing down economic progress. LDCs do not have sufficiently high

incomes to enable sufficient rates of saving; therefore, accumulation of

physical-capital stock through investment is low.

The

model implies that economic growth depends on policies to increase investment,

by increasing saving and using that investment more efficiently through

technological advances.

The

model concludes that an economy does not "naturally" find full

employment and stable growth rates.

2.3 Karl Marx Theory of Development

Karl

Marx, the father of scientific socialism, is considered a great thinker of

history.

He is

held in high esteem and is respected as a real prophet by the millions of

people.

Prof.

Schumpeter wrote,

“Marxism is a religion. To an orthodox Marxist, an opponent is not merely

in error but in sin”.

He is

regarded as the father of history who prophesied the decline of capitalism and

the advent of socialism.

The

Marxian analysis is the greatest and the most penetrating examination of the

process of economic development. He expected capitalistic change to break down

because of sociological reasons and not due to economic stagnation and only

after a very high degree of development is attained. His famous book ‘Das

Kapital’ is known as the Bible of socialism (1867). He presented the process of

growth and collapse of the capitalist economy.

Assumptions of the

Theory:

Marxian economic

theory of growth is based on certain assumptions:

1.

There are two principal classes in society. (1) Bourgeoisie and (2) Proletariat.

2.

Wages of the workers are determined at a subsistence level of living.

3.

Labour theory of value holds good. Thus labour is the main source of value

generation.

4.

Factors of production are owned by the capitalists.

5.

Capital is of two types: constant capital and variable capital.

6.

Capitalists exploit the workers.

7.

Labour is homogenous and perfectly mobile.

8.

Perfect competition in the economy.

9.

National income is distributed in terms of wages and profits.

Marxian Concept of

Economic Development:

In

Marxian theory, production means the generation of value. Thus economic

development is the process of more value-generating, labour generates value.

But a high level of production is possible through more and more capital

accumulation and technological improvement.

At the

start, growth under capitalism, generation of value and accumulation of capital

underwent at a high rate. After reaching its peak, there is a concentration of capital

associated with the falling rate of profit. In turn, it reduces the rate of

investment and as such a rate of economic growth. Unemployment increases. Class

conflicts increase. Labour conflicts start and there are class revolts.

Ultimately, there is a downfall of capitalism and the rise of socialism.

Video

Lecture Links:

Comments

Post a Comment